Oct 16, 2020

By Dylan O'Brien, AmeriCorps NJ Watershed Ambassador

On October 21, we are taking a moment to reflect on one of, if not the most important, resources on our planet: water, in honor of Imagine a Day Without Water. Water is a basic human need to survive biologically, but it is also quite crucial to how we function as a society. This day is not only important to step back and appreciate water, but also to learn about some of the mechanisms by which we utilize it and how we can use it more efficiently.

In our second blog in this series, we will be delving into what a watershed is and subsequently what a storm drain is, as well as how a storm drain differs from a sewage drain.

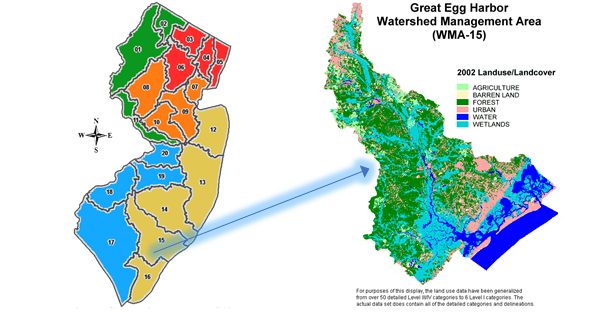

To understand the purpose of a storm drain, we must first understand what a watershed is and how it functions. A watershed is, as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “a land area that channels rainfall and snowmelt to creeks, streams, and rivers, and eventually to outflow points such as reservoirs, bays, and the ocean”. Everywhere we go is a watershed. Some are larger than others, but everyone lives within a watershed. The Atlantic County Utilities Authority (ACUA) is located in New Jersey’s Watershed Management Area #15 (WMA 15). There are a total of twenty in our state. Water will ultimately flow from the smallest watersheds into the larger watersheds and then eventually out into the ocean. Watersheds are teeming with wildlife, plants, and outdoor human activities such as kayaking and fishing. During heavy precipitation, such as rain or snow, flooding can occur due to these waterways overflowing.

In our modern society, rain and snow tend to fall onto what are known as “impervious surfaces.” These are areas such as: parking lots, concrete roads, sidewalks, mowed lawns, exposed soil, and the roofs of buildings. These structures all create what is known as “runoff” and this excess storm water is removed via storm drains. The issues arise when this water begins to flow towards the storm drains. Along the way, this water will gather harmful substances, such as: pet waste, road salt, pesticides, fertilizer, oil, grease, and litter. Even the soaps from washing cars, paint from houses, and dirt cause contamination. Sadly, just because certain products are labeled as “non-toxic” or “biodegradable” does not mean they are harmless substances. All of these things and more lead to negative impacts on the aforementioned plant and wildlife as well as the quality of the water itself.

Outside of pollutants, storm drains face another major problem: an identity crisis. These drains are often mistaken for sanitary sewer systems. Sewer systems do not receive any of the runoff mentioned in the previous paragraph, but rather the water from areas such as kitchen sinks and flushing the toilet. This water is sent through a series of pipes to a wastewater treatment facility. The ACUA manages a large amount of this type of water throughout WMA 15 at their very own wastewater treatment facility just outside of Atlantic City. Many of us have driven by this area, without even realizing it, however we have all certainly noticed the large wind farm on our way into the city.

While certain aspects of pollution are not within our complete control, we can change our habits and be more conscious of our surroundings. It is certainly within our abilities to limit pollution via storm drains and runoff. Some of the easier things we can do are as follows: do not leave pet waste on the ground, sweep our driveways and sidewalks to remove any harmful debris, use chemicals for treating our lawns properly and limit their usage overall, and finally do not dump trash down storm drains and remove any litter we see. Additional ways we can reduce storm drain pollution include: recycling our motor oil, washing our vehicles on grassy land or going to a car wash that we know will filter out the wastewater, and joining groups that mark storm drains more clearly for the general public to understand what exactly they are and what their purpose is.

All of this information can be a lot to absorb, and unfortunately the general public is not usually privy to this knowledge without seeking it out for themselves. The most important lessons to be learned from this discussion are as follows: storm drains are not sewer drains, and we have a responsibility to limit our negative impact on our storm drains and ultimately our watersheds.

Resources: